This article was reproduced with permission from Bloomberg Law. Published June 17, 2025. Copyright 2025 Bloomberg L.P. 800-290-5460. For further use, please visit https://licensing.ygsgroup.com/bloomberg/.

Barclay Damon’s Pei Pei Cheng de Castro and Jennifer Hopkins explain why the Supreme Court may be forced to step in and determine whether geofencing warrants in criminal investigations are constitutional.

As law enforcement increasingly relies on location data to investigate and prosecute crimes, a controversial investigative tool has come under constitutional scrutiny—the geofence warrant.

These warrants allow police to obtain location history data from technology companies about every mobile device present within a defined geographic area during a specific time window to identify potential crime suspects. Because these warrants don’t begin with an identifiable suspect, they have been said to “‘work in reverse’ from traditional search warrants.”

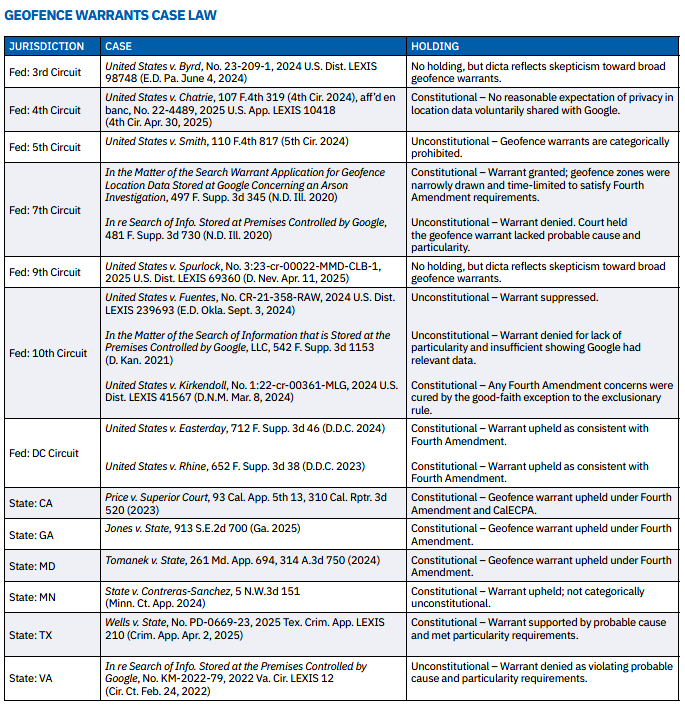

The validity of geofence warrants is now at the center of a federal circuit court split. The key question: Can the government constitutionally collect data on every person in a given area in the hope of identifying a suspect later?

Geofence warrants rely on a common digital practice: When users enable location services on devices, companies such as Google LLC and Apple Inc. collect and store that data. Law enforcement has increasingly tapped into these databases by drawing a virtual boundary around a specific location and, through a geofence warrant, requesting location data for all devices present during a defined time window.

This practice can subject hundreds of people who had nothing to do with the crime to investigation.

For example, in 2018, Arizona police arrested Jorge Molina on a murder charge based on a geofence warrant. But the real suspect—Molina’s stepfather—had been using a phone linked to Molina’s Google account. As a result, Molina spent six days in jail, lost his job, failed a background check, and lost the title to his vehicle because police impounded his car during the investigation.

Although companies such as Apple, Lyft Inc., and Uber Technologies Inc. have received geofence warrant requests, Google receives them most frequently—and is reportedly the only one known to respond. Since 2016, requests for geofence warrants have skyrocketed, comprising more than 25% of all US warrants served on Google. While initially used for serious crimes, they are now issued in routine cases, including property theft and vandalism.

Critics argue that geofence warrants undermine the Fourth Amendment by presuming everyone in an area is a suspect and only later sorting out who might be relevant. Some courts have echoed that concern, but others have held geofence warrants don’t cross the line.

In United States v. Smith, the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that geofence warrants are unconstitutional, describing them as “general warrants categorically prohibited by the Fourth Amendment.” The court applied Carpenter v. United States, in which the US Supreme Court held that individuals have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their long-term cell site location data.

According to the Smith court, the third-party doctrine—that people can’t expect privacy for information they have made public—couldn’t excuse a warrantless mass search of users’ location histories. The court also found that Google’s location history opt-in process failed to amount to meaningful consent. Although the evidence in Smith was admitted under the good faith exception, the ruling leaves no doubt: In the Fifth Circuit, geofence warrants are unconstitutional.

On the other hand, in United States v. Chatrie, the Fourth Circuit reaffirmed the constitutionality of such warrants, holding that the government didn’t conduct a Fourth Amendment search when it obtained two hours of location data through a geofence warrant because the defendant had voluntarily shared that information with Google. The court applied the third-party doctrine and distinguished Carpenter on the grounds that location history data, unlike cell-site location information, is collected only after a user affirmatively opts in.

Because the request was limited in time and scope and the data was knowingly and voluntarily provided, the court found no reasonable expectation of privacy. The en banc court reaffirmed that such brief, targeted, reverse-location searches fall outside Fourth Amendment protections.

Lower courts are similarly split, suggesting the Supreme Court may weigh in.

Defense attorneys challenging geofence warrants can draw on several arguments. First, they can argue that obtaining historical location data from Google is a search under Carpenter, which held that individuals have a reasonable expectation of privacy in detailed, long-term location records, even when stored by third parties. Like the cell-site location data in Carpenter, Google’s location history data can reveal intimate patterns of daily life.

Second, counsel can push back on the claim that users meaningfully consented to Google’s data collection. “As anyone with a smartphone can attest,” the Smith court noted, “electronic opt-in processes are hardly informed and, in many instances, may not even be voluntary.”

Third, they can challenge the warrants themselves as lacking particularity and probable cause. A warrant that authorizes a search of every person in a geographic area doesn’t describe with particularity the persons or places to be searched. Probable cause must tie the search to specific individuals or devices, not a broad area with no individualized suspicion. The Smith court said problems make geofence warrants “constitutionally insufficient.”

Adding another wrinkle to the debate, Google announced in December 2023 that it would change how it stores users’ location history. Instead of saving this data on company servers, Google will now store it only on users’ individual devices unless a user chooses to back it up to the cloud. The change affects the detailed, timestamped records of where a user has traveled, collected when location history is enabled. Unless backed up, this data will be automatically deleted after 90 days. The rollout was expected to be gradual, starting in May 2025.

This policy change could limit law enforcement’s ability to obtain historical location data through geofence warrants. Without centralized access to years of stored data, prosecutors may no longer be able to serve broad geofence requests to Google and receive long-term records.

Until the Supreme Court decides to hear this issue, courts and litigants must grapple with whether geofence warrants strike the right balance between investigative utility and constitutional privacy. Defense counsel should be vigilant in challenging these warrants and preserving the issue for appellate review both within their own circuit and in anticipation of eventual Supreme Court resolution.